I’ve spent time writing, designing and playing “pen & paper” role-playing games. I learned a lot working on them, both about story and games. (This is where I began focusing on how some things that work in one medium might not work in another medium! A play is not a novel is not an RPG is not a movie!)

Delving deep into MMOs, I’ve discovered they’ve shed a lot of the assumptions that many paper RPG publishers and players had, and break free of some of the “culture” of RPGs:

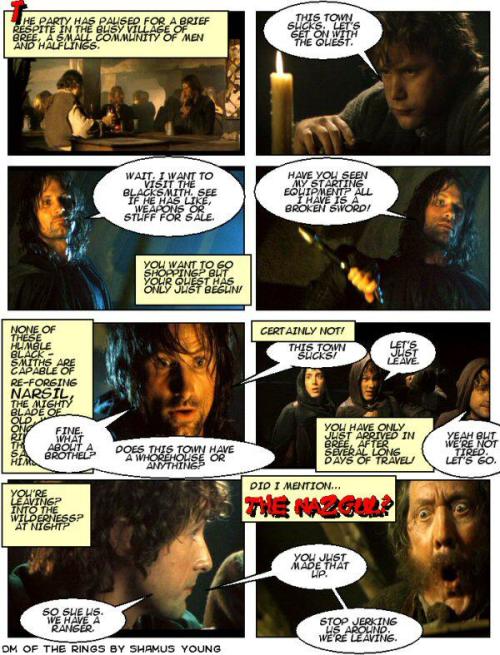

For such a fun, innovative way of building a narrative through group effort, the players usually don’t have much input.

In traditional games the Players make the “characters” and the GM makes the “story”. The trick is this: the whole point of a character in a story is to make decisions. That’s what drives a story and that’s how real character is revealed — what does a person choose to do.

Now, often in role-playing circles (and other circles as well), people confuse characteristics with character. Character is the choices a person (or character) makes. That’s what we used to mean by the word “character” when talking about people, and it’s still a standard wrench in a writer’s tool-kit.

But most RPGs didn’t know what to do with that because the GM had already built the “story.” (Scare quote on purpose, but with apologies… For reasons to be revealed.)

If the GM already knows that a series of events might lead a character to one specific end, the Players really have little control over the choices their character can make.

If we’re playing a Space Opera and my PC is a farm-boy from a backwater world battling a horrible Villain, and the GM whips out the reveal at the table that the Villain is actually my characters’ father — it’s a thrilling moment, because WHO KNOWS WHICH WAY MY CHARACCTER IS GOING TO JUMP?

But if the GM has already decided that my character and the badguy will be fighting side by side against the rest of the Player Characters there CAN’T be a choice. More importantly, the GM will sort of shoehorn me with subtle signals (often involving unspoken rewards or punishments) to have my guy side with the Villain — because that’s the cool scene he had in his head. But it might not be what I consider a cool scene.

So, what do we consider “role playing” in such a game? Basically, people play the CHARACTERISTICS of the PC. The GM says, “Here’s such and such a situation, and basically I know how it’s going to lead into the next scene, but what you’re going to do is play out the behaviors of your characters,” (not real, meaningful choices that can drive the narrative in unexpected directions, but simply the behaviors.)

This is where we get the focus on “talking in character,” the funny voices, only knowing what you know in character — because it limits the Player’s input into what actually change the shape of the tale.

But, again, if the Players are playing the characters they’re being robbed of one of the most important elements of creating a character — “What does the character do when the hammer comes down? When the tough choices have to be made, does Sheriff Brody cave to the will of the townspeople in Jaws, or does he take action to go public? Does Ripley flee when the space marines are getting chewed up, or does she put herself in harm’s way to save them?” And so on.

Note that the GM’s attitude often is, “Of course the player will put her character in harm’s way to save the space marines” when “plotting” and RPG adventure.

But what about when the character doesn’t want to? We all seen it happen a gazillion times. The responses vary — but they contain:

- The GM’s brain shutting down for five minutes as he tries to re-jigger the plot;

- the GM politely asking the Player to play along;

- the GM sort of bullies the Player with back-handed logic (“Well, your character would go save them, you know”)

- the GM has the aliens attack the PC anyway, no matter what ridiculous lengths the Player has the PC go through to get away;

- anger sometimes erupts at the table;

- sometimes there’s hours of post-game angst over the phone and emails.

[Please do check out Shamus Young’s fabulous DM of the Rings.]

Note that the key issue her is all about the Player simply not being allowed to make a vital choice for the character for fear it will ruin the game or the story. After all, we know what a character “should” do — right?

Well, no. Again, what a character chooses to do is what reveals the character. Should Michael Carleone have become a crime lord in his father’s footsteps? Should Ripley have stopped Dallas from bringing an infected Kane onto the Nostromo? And so on.

Characters make decisions, flip flop. There are consequences to their actions and then, in light of those consequences, they make new choices..

In this way, a role-playing game session would be more of a lively game of “what the hell is going to happen next?” The Players make choices for the PCs. The GM tosses out the next set of hard decisions on the fly. And when it’s all over we have a story we could not have guessed at.

Of course this blows “The Party” model of play right out of the water. But why should the party have to stay together. Only one person at the table can ever speak at one time anyway! Whether their fictional characters are in the same imagined space or not doesn’t change that. You still have to rotate around the table.

In fact, a whole bunch of assumptions have to get shattered — the key one being: “This wouldn’t work.”

The questions show up fast, “How can there be a story if the GM doesn’t have a story?” “What if one of the Players has her PC run off to China?” “You could do this, but you would need ‘advanced’ Players.”

The truth is, No.

It works just fine. It works fine for beginners. The games are a blast. Here’s a list of some small games that have been thought through packed with rules and techniques to do exactly what we’re talking about:

Sorcerer

Dogs in the Vineyard

The Mountain Witch

The Burning Wheel

InSpectres

The Riddle of Steel

HeroQuest

There are more.

There’s no way to summarize all these games, of course. So I’ll just say this:

The players in these games write down what is important to THEM. The GM still creates the world and backstory and the PCs with secrets. But the GM is also responsible for utilizing the narrative elements the Players create during character creation. For example, in Sorcerer, there’s a thing called a Kicker. If I’m creating a Player Character I might say, “My character kicked my son out of the house 20 years ago when he suspect my character murdered my wife (which, in fact, he did). On the day the story starts, my son comes home asking forgiveness.”

The first question to be asked is, “Does my guy let the son into the house?”

But after that there are more questions: Does the son have an agenda? Is he really he for forgiveness or vengeance? Is my wife’s ghost going to start talking to my son if he comes in the house? Given the genre and the other back story information created by the players and the GM, the GM gets to make up LOTS of stuff. He just isn’t making up the plot.

He’s simply making up material to let the Players make tough choices with emotional and thematic impact. You know, like a story.

But, of course, this means a new distribution of power among the players. The GM isn’t building a channel to dive the characters through toward a certain kind of ending. For all we know, in the Space Opera, Luke does end up fighting his friends because of his desperate love for his father. (In this kind of game play these kinds of choices are valued. It’s not a betrayal of the party. It’s a love of the story.)

The GM can’t give little clues about what is supposed to happen, because he has NO IDEA of where the story will be in three hours.

There’s a tradition of RPGs that says you simply don’t play that way. And that’s great for folks who want it. But other people are very excited about pushing more power amongst the players and having a great time doing it.

Now, back to MMOs…

In a game like World of Warcraft, the game’s designers have established “quests” for your character, but a lot of how you go about doing it is your business. You can try it alone, you can gather a party, you can be loyal all the way through the quest, you can abandon your fellow adventurers along the way. You can retreat when you want, turn down a quest if you want. You can set your own goals if you want.

This is a lot more freedom than a lot of players got when they sat down the a GM to “play a story.” In fact, a lot of RPG sessions play pretty much like the story in a First Person Shooter or Survival Game and many RPG games: the player is led from one cut scene to the next, needing to defeat a bunch of bad guys, and then watching the next cut-scene. In this way, the players are being told a story, but they’re not really participating in it since they have no impact on it.

Not so in an MMO, where the players pick their actions and goals without needing to please anyone but themselves. They don’t have to stay in a group, they don’t have to follow “the story.” They don’t have to do anything, really. But… because they are interacting with other, real people, their choices carry consequences. Doing a good deed might be rewarded later. Being an ass-hat might mean trouble later.

Eve Online carries this even further. Set in a future world of space travel, commerce, mercenaries and exploration, the players are let loose without any preplanned agendas at all. There is an environment (computer controlled characters, asteroids to mine, planet-sized economies to run or ruin) and there are the other players. What a player decides to in Eve is his or her own business.

Unlike World of Warcraft, there are no pre-planned quests for the characters to pursue. Players are absolutely left to their own devices to figure out what to accomplish and how to go about doing it. This can take a toll on new players, who are left without any guidance. But it also means almost unparalleled freedom when it comes to the player choosing what actions his character will take, and so what kind of story the player will “tell” with the character.